Vladimir Putin pretends that everything is under control. The West has over-imposed sanctions on Ukraine and is primarily responsible for the grain crisis and energy shortage. But this discourse has a downside.

These are busy times for Vladimir Putin. One minute he has intense conversations with Iranian and Turkish leaders in Tehran, and the next he talks for hours in Moscow with ambitious young Russians about “powerful ideas for a new age.” Putin seems to be in his element. He talks a lot, makes jokes and regularly makes fun of our “Western partners”.

Most noticeable in all of these conversations is that the Russian president carefully avoids the word “Ukraine” whenever possible. During the two hours that Putin spoke with a select few in Moscow about innovation and Russia’s bright future, the name of the neighboring country was not uttered once, nor by Putin, nor by the rest of the audience. A little earlier, a Russian missile exploded in Kharkiv, 600 km away. Three people were killed, including a 13-year-old boy.

work as usual

“Business as usual” is the message Putin radiates wherever he goes with his body language. He and his entourage systematically emphasize that the “special military operation” in Ukraine is going according to plan. Thus the battle in Ukraine became routine in Russia. Any opposition and any criticism or doubt will be nipped in the bud.

According to Moscow, Western sanctions have had no effect and will affect only the population in the countries that have declared them. It is said that Russia has faced hotter fires and will not come to its knees and will eventually emerge stronger from the current turmoil. The suggestion that Russia is internationally isolated has been vigorously mocked in the Kremlin and on state television.

alternative world order

“We know that our African colleagues do not agree with the overt efforts of the United States and its European satellites to impose their will on everyone,” Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov wrote in an article that appeared simultaneously in several African newspapers on Friday. Putin told his audience in Moscow that the world is currently going through “significant and irreversible changes” and that there will be a “harmonious and fairer” alternative to the unipolar world order that has existed until now.

Putin’s visit to Tehran last week was supposed to add color to these words. Talks dealt with Syria, the suspension of grain exports from Russia and Ukraine, and the prospects for a new north-south transport route. This should connect Russia with Iranian ports on the Persian Gulf and thus facilitate the delivery of Russian raw materials, for example, to Asian customers, which makes sanctions more difficult.

Special relationship with Turkey

For Russia, Iran is the prime example of a country that has been able to withstand Western sanctions for decades, and is thus a natural partner. Russia has enjoyed a special relationship with Turkey, a NATO member for years. Putin and his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdogan have known each other for a long time, and have good personal contact, although there are sometimes heated differences. Relations with Erdogan are in line with Russian policy, which favors maintaining direct contacts with people or countries that follow their own, and sometimes skewed, path within the Western alliance. It is Russia’s proverbial foot in the door.

At the same time, Putin misses no opportunity to stress the extent to which the West has manipulated sanctions. He argues that it is not Russia, but the West, that is responsible for the problems that have arisen with grain exports and the prospect of starvation in parts of Africa and Asia. And not Russia, but the West itself has caused the current energy problems by blindly focusing on alternative energy and blocking the operation of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline.

The central message here is that the West and the world cannot ignore Russia and that Moscow, whether sanctions or not, has enough sticks to respond with. For example, by cutting off energy supplies to Europe (gas will flow through Nord Stream 1 again, no one knows for how long) and instead strengthening ties with China, it is often a “turn east”.

North Korea

All this discourse has a downside. It cannot hide that criticism of Russia’s actions is not limited to the West. In early March, the vast majority of UN member states (141 out of 193) supported a resolution condemning Russia and calling for the withdrawal of its forces from Ukraine. Overt support for Moscow comes only from countries such as Syria, North Korea, Belarus and Eritrea. Many countries wisely keep a low profile, such as pragmatic China, which, while cherishing its good relationship with Russia, does not want to harm its most important economic relations with Europe and the United States.

China needs Russia much less than the other way around. But “turning east” is largely wishful thinking. China cannot compensate for Russia’s crucial Western technology loss, more than the decline, now and in the future, in Russia’s massive oil and gas exports to Europe. Russia’s dependence on China will increase. The consequences of Western sanctions on the development of the Russian economy and the state budget will be far-reaching in the long run, no matter how much Putin tries to downplay them.

discord

It is expected that the continuation of repeating this frivolous message will sooner or later sow discord among Western voters. The same is true of the ongoing tension over Russian energy supplies and its consequences, such as significant reductions in energy consumption. Putin is convinced that time is working in his favour, and that the tide will turn against him before sanctions really start to hurt.

“Creator. Award-winning problem solver. Music evangelist. Incurable introvert.”

More Stories

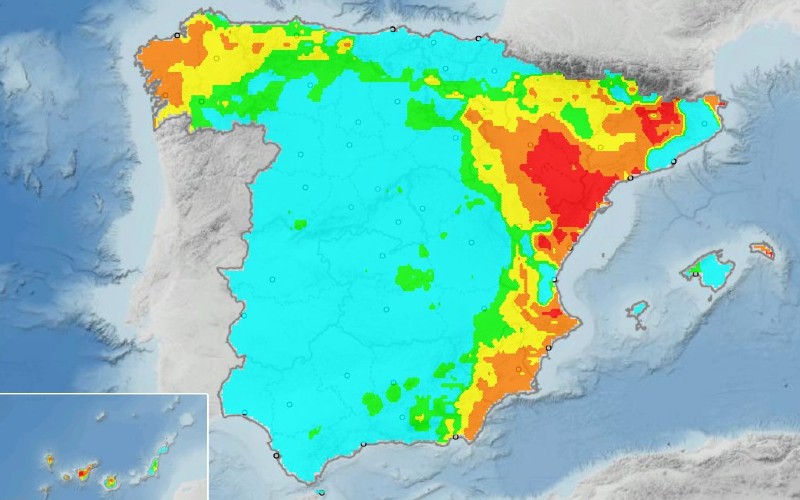

The Spanish Meteorological Service warned of the danger of forest fires in several areas

Exclusion of the “Animals and Transparency” organization from the elections: “Shame”

McCarthy 2.0? President Mike Johnson's plans to provide aid to Ukraine have led to a crisis within the Republican House of Representatives