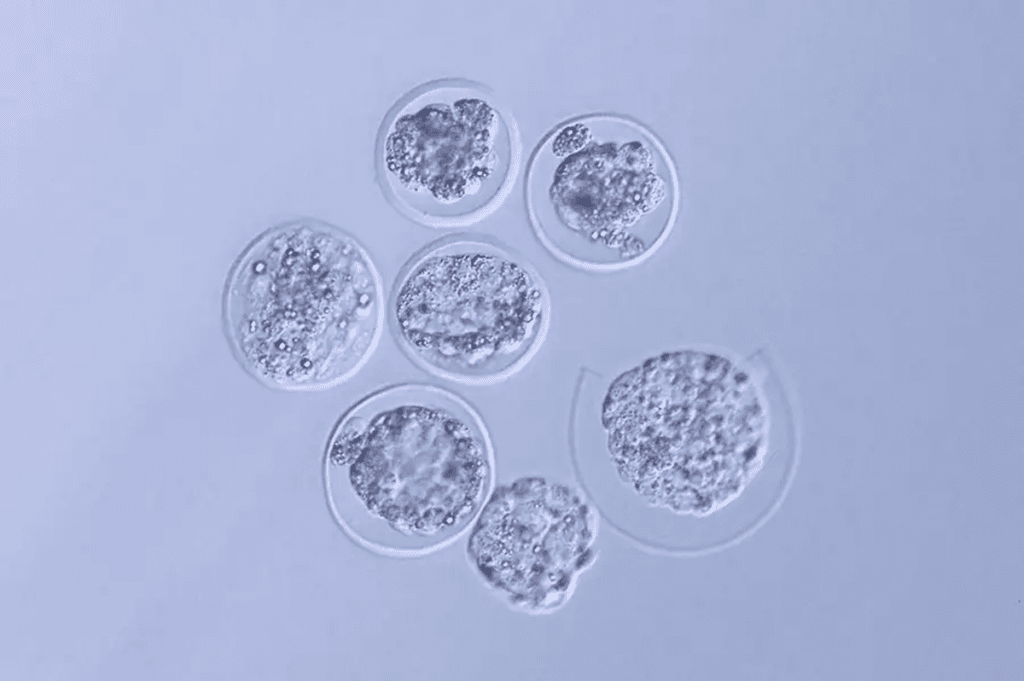

Mouse embryos have been successfully raised on the International Space Station. Experience indicates that the early development of fetuses is not disrupted by weightlessness and the high dose of radiation.

Mouse embryos were first produced aboard the International Space Station. Researchers want to know if it is safe for a person to become pregnant in space.

“A future trip to Mars will take more than six months,” says the biologist. Teruhiko Wakayama From Yamanashi University in Japan, who search Drove. “We want to make sure that anyone who is pregnant during this journey can have babies safely.”

Read also

“What people have long forgotten is still written on the trees.”

With her tree drill, Valerie Truitt examines forest giants and reconstructs what they lived.

SpaceX rocket

Wakayama and his colleagues conducted the first steps of the experiment in their laboratory on Earth. They took embryos from pregnant mice and froze them. The mouse embryos were at an early two-cell stage of development.

In August 2021, the frozen embryos were sent to the International Space Station aboard a SpaceX rocket. These embryos were contained in devices designed by the Wakayama team so that astronauts could easily thaw the embryos on the space station and grow them for four days. The astronauts then preserved the embryos using chemicals and returned them to Earth in a probe.

The fetus and placenta

Wakayama says the embryos were implanted for only four days because they could no longer survive outside the womb. His team studied the returned embryos to see if their development was affected by the high levels of radiation and so-called microgravity on the space station.

The fetuses did not show any signs of DNA damage as a result of radiation exposure. They also showed normal skeletal development. This made it possible to distinguish between the two groups of cells that form the basis of the fetus and the placenta. It was previously thought that microgravity could affect the ability of embryos to separate into these two cell types, Wakayama said.

Artificial insemination in space

It remains uncertain whether later stages of fetal development will be disrupted by stay in space. In previous research, mice were sent on a NASA space flight for nine to eleven days during the second half of their pregnancy. Back on Earth, these mice gave birth to pups With the common weight in the world. This indicates that the puppies have developed normally.

“Based on this and our results, mammalian reproduction in space may be possible,” says Wakayama. However, he said it is still unknown whether it would be difficult to give birth to a full-grown mouse or human baby in microgravity.

Wakayama's team will now test whether mouse embryos sent to the International Space Station and then returned to Earth can be implanted in female mice and then developed into healthy offspring. This will provide more evidence about the viability of embryos exposed to space radiation and microgravity. The researchers also want to test whether sperm and eggs from mice sent to the International Space Station can be used to create embryos in space via artificial insemination.

“Total coffee specialist. Hardcore reader. Incurable music scholar. Web guru. Freelance troublemaker. Problem solver. Travel trailblazer.”

More Stories

Elbendamers in the Sun: What a Wonderful Little Village

European Space Agency – Space for Kids

This is how to protect your eyes in the summer, according to an ophthalmologist