Anton Jäger is a historian of political thought at the Leuven Institute of Philosophy. His column appears bi-weekly on Wednesdays.

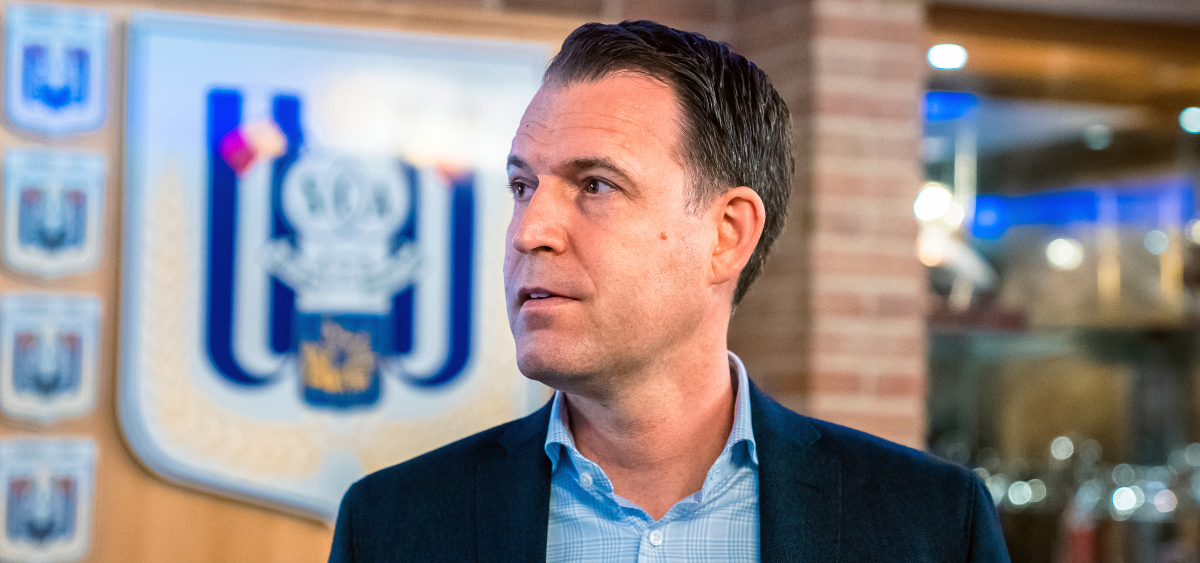

It wasn’t a pretty sight. I decided a month ago latest news To conduct a survey among 1,500 Flemish teachers. The sector has been allowed to put its minister Ben Witts (N-VA) and his latest policy on the agenda. The “poor” report speaks volumes: 4 out of 10 gave the current minister 0/10, and the rest turned to television. The minister won’t even get a damned B certificate.

There are severe teacher shortages, falling test results, tampering with secondary enrolments, empty learning rewards – the minister once appointed to lift Flemish education out of the doldrums has not had a glorious career. Wits usually defended himself by attacking: teaching had become a hobby for the unemployed, no longer a profession, merry teachers had spoiled training, and teachers could not fulfill the educational tasks of parents. The blame was again placed indirectly on the teacher.

Luits inadvertently made one point: that the discussion about education in Flanders is taking place in a remarkably narrow way, especially now that the sector has been bombarded with increasingly extreme expectations from the surrounding community. British Prime Minister Blair said “education, education, education” in the late 1990s, when his government was focusing everything on education. For Blair, a successful school career became a panacea for every social ill.

Such a one-sided focus on education at the expense of other policy areas is not that old. In the 1920s, the left-wing politician from Weimar, Werner Scholem, spoke of the so-called The illusion of formation. The idea was that the lower classes could get themselves out of trouble by studying hard.

Convenient scapegoat

Scholem thought that was a weakness. Instead of fighting collectively for their rights, workers will be forced to rise individually from their class. Consequently few individuals will escape their social fate. The larger social issue remained unaddressed.

The discussion about Flemish education also suffers from such an illusion. By making the education debate exclusively about teaching, the sector becomes a convenient scapegoat for problems over which the teacher alone has little control. Whether it’s inequality, reading, morals, language skills, or employment: the classroom is always disconnected from the wider world of which it is a part.

This has a major distracting effect. For example: by making education the exclusive driver of social mobility, the difficult issues surrounding redistribution and poverty are rarely discussed. The social issue is limited to the issue of education. Employers are also increasingly shifting the cost of training to the state, while retraining in the workplace is becoming rare.

Trapped

A society in which book sales are declining makes the teacher exclusively responsible for reading skills. A government channel that regularly broadcasts common languages cannot expect its students to speak Dutch without an accent.

Thus, the teacher is attacked from both sides. On the one hand, by a society that values his work less but has high expectations of the profession. On the other hand, a country that does not want to spend a lot but still wants to achieve good international rankings.

Waits himself did very little to turn the tide. In 2021, it was announced that 121 million euros would be saved in the education sector. The attractiveness of teachers’ wages has not increased compared to private sector amounts.

Amazing amounts

At the same time, more and more students flocked to Flemish schools. The result is summed up by a term called in the sociology of work “acceleration”: instead of expanding the employee base, the existing team is asked to accommodate new demand. This means working longer and harder, for the same pay.

Teachers in Dutch-speaking education in Brussels have an annual budget of €50 to purchase classrooms, while long summer holidays are quickly lost in classroom preparations. These remain staggering sums in a country officially considered one of the richest regions in the world.

“Total coffee specialist. Hardcore reader. Incurable music scholar. Web guru. Freelance troublemaker. Problem solver. Travel trailblazer.”

More Stories

European stock markets are expected to open lower.

Bosman transfers the company to the Finns.

Belgian businessman saves Flemish stores from collapsing fashion chain Scotch & Soda