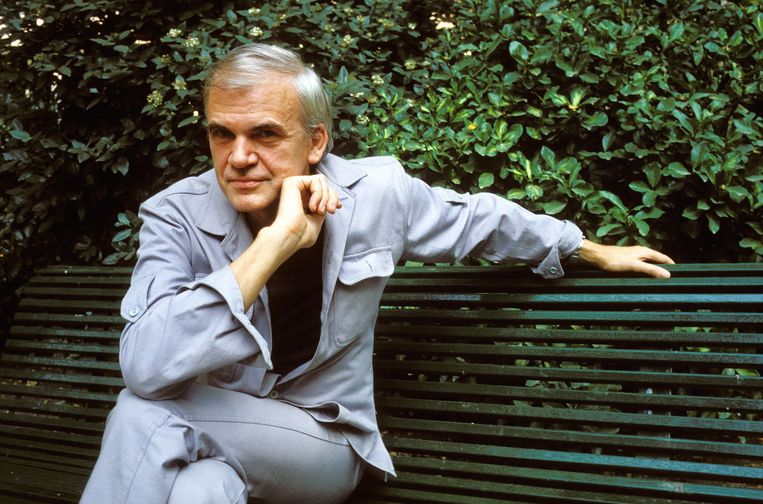

With the death of the Czech writer Milan Kundera (94) – who preferred to portray himself as a French novelist – world literature has lost its indisputable image of the novel of ideas.

Once upon a time, in the mid-1980s, reading Western Europe seemed almost mass The unbearable lightness of being (1984) to devour. When the successful film adaptation by Philip Kaufman was added in 1988, starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Juliette Binoche, this philosophical love novel set against the backdrop of Prague Spring (told from four different points of view) grew into a kind of bible. Until now, the title still lingers in the language. Ironically, Milan Kundera thought the film was a disaster “because it didn’t respect the spirit of the book”. He has since banned film adaptations.

The award-winning Kundera, always just missing out on a Nobel Prize, had a recipe for intelligent, accessible novels in which he turns out to be a satirical seismographer of love and the human condition. Novels like life elsewhere (1973), The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1978) or immortality (1988) offered almost intuitive depth, mixed with humor and irony, and refreshing insights into the emotional traffic. Alain de Botton said: “Perhaps most impressive, given that greatness in modern literature is almost synonymous with ‘annoying’, is how entertaining Kundera writes”.

Writers such as Julio Cortázar, Patrick Modiano, and Philip Roth admired him. It is no coincidence that Kundera found the postmodern novel of ideas the chosen means of understanding the full life: “Every novel tells the reader: ‘Things are more complicated than you think.’” Kundera positioned himself in the tradition of Diderot, Cervantes, Kafka or Robert Musil.

hoax scatters

Kundera – whose death had already been announced several times by the publishers of the hoax – died yesterday, July 11, in his Paris apartment after a long illness. In France, where he ended up as a Czech refugee in 1975, Kundera led a reclusive life with his wife Vera, once a popular Czech TV presenter. Since 1985 he has been constantly fending off interlocutors and snoopers. However, France cherished him as a treasure, especially when he was granted French citizenship in 1981 and began writing directly in French in gratitude.

The fact that his work was included in the Pléiade glossy series in 2011, as the first living author, was an event. Occasionally someone may vouch for a brief encounter. French journalist Mathieu Galli described Kundera by saying, “His accent gives him infinite charm and those blue eyes put you in a kind of orbit around the Earth. He has something of a boxer and a pope. Warm and protective. It gives you physical confidence. The opposite of his books.”

Libertine Erotica

Born in Brno, Czech Republic, Kundera found it all on her own “A joke with a “metaphysical meaning” that he saw the light exactly on April 1 of the year 1929. The talented son of a piano teacher – as reflected in the musical polyphony of his works – initially had lofty ambitions as a poet, and studied screenwriting and directing in Prague. Kundera followed in the footsteps of the Communists who came to power in 1948, and was not averse to some opportunism in publishing his early writings. But especially with the vile the joke (1965, praised by the French poet Louis Aragon) and humorous stories from likes funny (1968) Sneaking into the bitterness of communist delusion. Conflicts with the Czechoslovak authorities escalated: in 1970 Kundera was expelled by the Czechoslovak Writers’ Union and subjected to intimidation and shadowing.

Kundera fled the scene after the brutal Prague Spring crackdown in 1968 by the Soviet Union. In the end, Kundera, “the banished satirist of totalitarianism,” according to the Associated Press, lost his Czechoslovak citizenship in 1979, only regaining his Czech citizenship in 2019. Every translation into Czech came against njet. Tragic though it may be, emigration to Western Europe heralded a “literary renaissance” for Kundera, in his words. Le Monde Certainly, “certainly after the fall of the Berlin Wall and a resurgence of interest in Central European literature”.

With novels like The unbearable lightness of beingAnd life elsewhere And The Book of Laughter and Forgetting He toyed with themes such as (liberated) eroticism, satire, mortality, rejection of kitsch, and nostalgia.

Student’s house

Kundera still hated autobiographical interpretations. “All novels in all ages deal with the mysteries of the self,” he confesses, but “the novelist demolishes the house of his life in order to build the house of his novel with those stones,” he said. The art of the novel (1986). However, the author got into close quarters when it was the Czech weekly newspaper respect It accused him in 2008 of having denounced a former young airman in the 1950’s as a Communist police informant and commandant of a student home. Kundera adamantly denied this, calling it “writer’s murder”.

Recently, Kundera has faced another headwind: British author Jonathan Coe accused Kundera in 2015 of Watchman Overwhelming “male orientation”: “I avoid using the word misogyny because I don’t think Kundera hates or is hostile to women, but only sees the world from a male point of view.” Coe felt that in the long run this could damage his reputation. Le Figaro It is noted that at a later time, even novels with a philosophical tint, such as Slowness (1995)And ignorance (2001) and Feast of insignificance (his latest work from 2014) was “chatty” and “full of rhetorical tricks”.

“Friendly communicator. Music trailblazer. Internet maven. Twitter buff. Social mediaholic.”

/s3/static.nrc.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/web-0105ecofed.jpg)

More Stories

Candice Martens tells all about second date: 'Jilted'

This is how Kate Upton looked when she was 19 years old without a shirt (video)

Eddie Blankart suffers from health problems: “It could end fatally”